From the time electricity first reached homes and buildings until today, there has been a major development in how electricity use is measured and priced. As the energy system is transformed, there are now completely new demands for smarter price signals, not only from the electricity market but also from the electricity networks. How do we design electricity network charges that are both cost-effective and non-discriminatory and that in reality also steer towards more efficient network utilisation - without creating sub-optimisation in the electricity system? Is the power tariff that is now being rolled out in more and more electricity networks the right way to go?

Network charges in the beginning

When Thomas Alva Edison started distributing electricity to New Yorkers in the late 1800s, households were charged based on how many light bulbs they owned. There was nothing strange about that because most homes used electricity only for lighting. Electrical appliances were too expensive for the average person.

In Sweden, a pricing model was introduced in the 1930s whereby the fixed charge for electricity was calculated on the basis of the number of so-called tariff units. For a household, one tariff unit applied per room. For companies, the number of tariff units depended instead on the installed capacity of electric motors etc. When tariff units were introduced, the fixed cost was around 75 per cent of the customer's grid cost, but this had fallen to 25 per cent by the time it was phased out. In the 1960s, the pricing model that has been dominant until today was introduced: the hedging tariff. With fuse tariffs, the electricity customer's main fuse determined the fixed charge instead.

Power tariffs take centre stage

Today, Swedish electricity network charges often consist of a fixed and one or more variable components. By 1 January 2027, all Swedish electricity network companies must have introduced a new pricing model that includes a power tariff, or power charge, which is time-differentiated. A power tariff is a variable tariff component based on the power you use. With time differentiation, it also matters when you use the power.

A common theme for the majority of power tariffs that have already been implemented is that they are based on the highest hourly value in a month, or an average of three or five hourly values. Some DSOs already have a time differentiation on the power tariff, for example that the power tariff is only applied at certain times or that it is higher during certain times (typically weekdays, 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. during November-March). Further parameters that DSOs can tweak are whether they reduce their fixed charges and change the transmission charge in any way when the power component is introduced. If the customer controls their electricity use based on the electricity network charge, it is of course the total cost that they want to optimise, and then the power charge can be a more or less large part.

The impact of the effect

Electricity network tariffs are intended to steer towards efficient utilisation of the electricity networks and the idea is that power tariffs should be a means of achieving this. This is of course a good idea and much needed given the low utilisation rate of our electricity networks. Distribution substations in the EU are used on average only 10%, with a spread of between 2% and 21%. Add to this the increasing need for investment in the electricity networks, and efficient utilisation of the electricity networks seems to be an obvious goal.

Of the grid companies Sigholm has spoken to, however, few have noticed major effects on customers' consumption profiles after introducing a power tariff. Sollentuna Energi och Miljö is one of the exceptions. It was one of the first companies to introduce the tariff model back in 2001, and according to the company, the power tariff has helped to connect 17,000 new customers over the past 20 years without increasing the regional network subscription. At the same time, the company sees that the power tariff has controlled electric car charging in such a way that they have not had to increase the capacity of the network stations. Sollentuna's power tariff is based on the three highest hourly average values during a month. The power tariff has a higher price level during November-March and is only charged on weekdays between 7am and 7pm, the general peak time for Sollentuna's electricity network.

Blunt tool to create local benefit

A capacity charge designed on the basis of the general peak time in the network can create benefits towards overlying networks, but how effective is it in addressing real capacity challenges in the local network when these are not homogeneous throughout the network?

To give an example, let's imagine a small summer cottage area under a substation where the peak load time is in summer. Suddenly one of the cottages is converted to year-round living with electric heating and for the only permanently resident electricity customer, the power consumption is thus at its highest in winter. The peak load for the specific substation, however, is still in summer. At the same time, the local network company has a time-differentiated power charge based on the entire network's peak load time - winter time. The year-round resident in the summer cottage area therefore has to pay heavily for his winter behaviour, even though it is not a problem for the specific substation. Can we then say that we have created a more efficient network utilisation? If the customer's behaviour is not a problem, why should it be penalised?

In the summer cottage area, we can now add another layer: it has become a trend in the area to install solar panels on summer cottage roofs. Since the electricity grid company has no feed-in tariff and the power tariff steers towards reduced power consumption in winter, there are few incentives for prosumers to increase their own use of solar power, apart from the electricity market's price signals. Much of the solar power is therefore fed into the grid, creating completely new peaks in the load on the electricity grid. Once again, the feed-in tariff has not created any local benefits.

The urgent needs of the electricity system

Speaking of solar, another relevant question is whether the power tariff really creates socio-economically profitable decisions in an electricity system with increasingly renewable generation? To answer this question, we need to introduce the concept of residual load. The residual load can be calculated as the total electricity consumption minus the electricity produced by renewable energy sources. In addition to renewables, it can also include non-flexible generation such as nuclear power and some hydroelectricity (run of river or spring flood) which is simply difficult to regulate at short notice. The residual load is important for understanding and planning the operation of the electricity system as it affects the need for flexibility and reserves in the system. A power system with a high share of renewable energy and non-flexible generation must have the capacity to quickly increase or decrease generation or consumption from different resources to balance the power system. A negative residual load is highly correlated with low or negative electricity prices. That is, times when we could benefit from a little more consumption to balance the system.

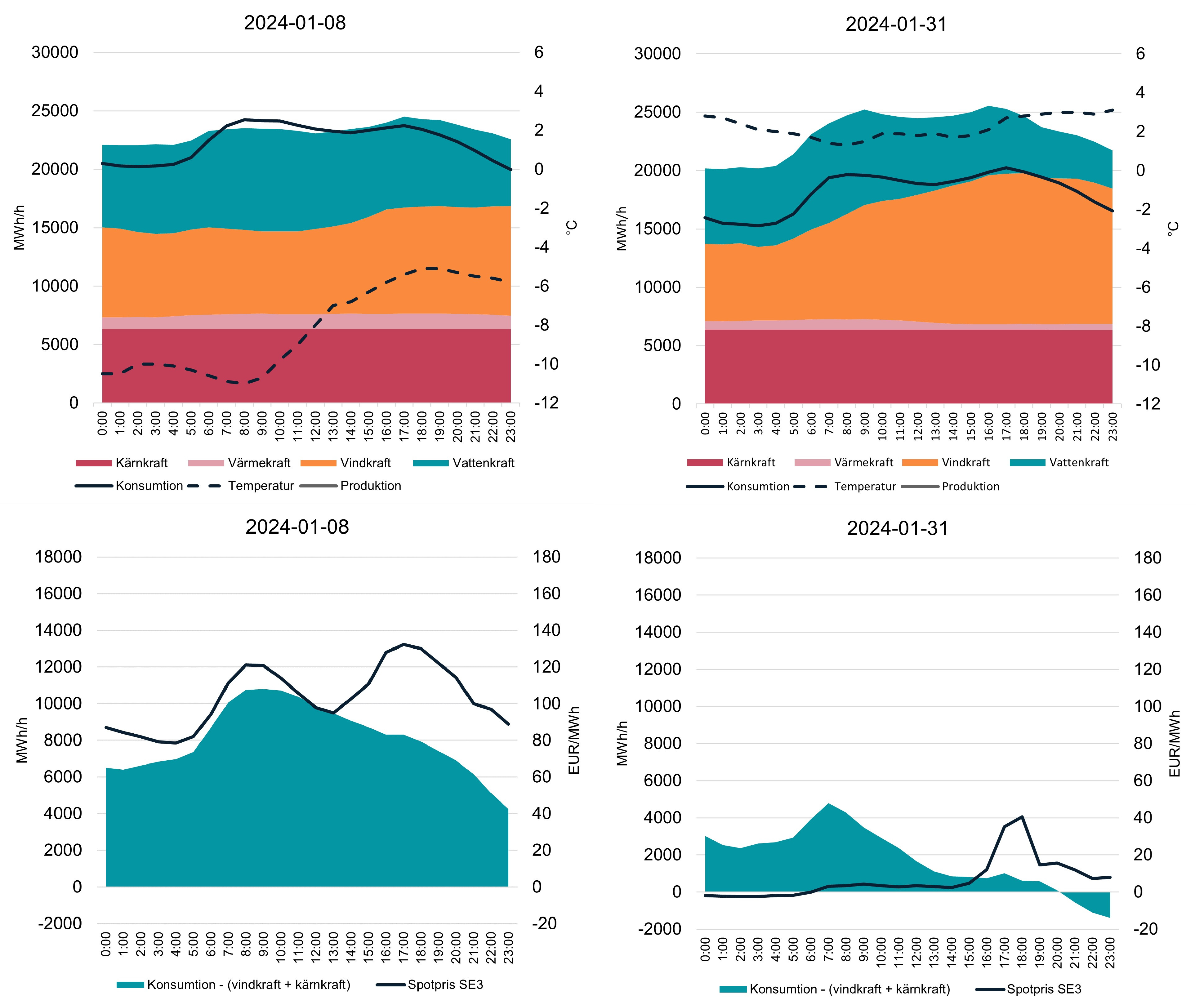

This can be illustrated by two different days in January 2024: 8 January was a cold winter day with high electricity consumption and low wind power production. Overall, this meant smaller margins between production and consumption and relatively high electricity prices as a result. Just over three weeks later, on 31 January, the situation was different. The weather was mild for the time of year and Sweden had a production surplus that was largely due to high production from wind power and non-flexible nuclear power. The production surplus contributed to low and occasionally negative prices in bidding zone 3. Here, then, we have two winter days with major differences in the situation in the electricity system, and with different control signals from the electricity market. But what control signal would be generated by a power tariff in this context?

Now think again about the holiday home area. The area's only year-round resident has now installed an electric car charger with smart control against the spot price. Let's say it's 31 January. If the customer had not had to worry about their power charge, they could have run full blast on charging during the hours when Sweden had a production surplus, balanced the electricity system and thus also been able to charge their electric car with electricity with a low carbon footprint. This would have been good for the electricity system, good for the customer and perfectly fine for the electricity grid, as summer time is the dimensioning period for this particular grid station. Is the customer acting in a way that is desirable from the perspective of the electricity system when taking the power tariff into account? Probably not, if the power tariff penalises the customer for high power consumption when the electricity system needs it most.

Electricity network tariffs that send the right signals

High prices should signal a real shortage situation, both in the electricity market and in a natural monopoly such as an electricity network. In order to create an electricity network tariff that reflects shortage situations, the electricity network company must know under what conditions, and at the same time where in the network, shortage situations arise. The power tariffs that are now being rolled out by more and more electricity network companies are a standardised way of trying to price the space in the network. They can contribute to a general reduction in power consumption - to ‘flatten the curve’. At the same time, as shown in the example above, there is a risk of sub-optimisation for the whole electricity system.

A more dynamic pricing system would be more optimal, where electricity network use should cost when a price signal is really needed, and that it is based on where in the network you as a customer are located. On Gotland, a project will start this summer to test just that: location- and time-specific price signals based on the load in each network station. Back in 2020, Energimarknadsinspektionen proposed that localisation signals should be included in the design of electricity network tariffs. It received a lukewarm reception, but with its brand new flexibility strategy, it is now reviving that idea too.

Measurement methods evolving - power tariffs soon to be a thing of the past?

In Sweden, we have had an intense period of roll-out of smarter electricity meters in recent years and from 2025 we will move to quarter metering. Customers are also being given more and more opportunities to monitor their electricity consumption in real time. Smart meters are just the first step on the electricity network companies' digitisation journey; other digitisation initiatives are now also taking place in the networks. For example, the electricity network company Ellevio is now rolling out an extensive programme to digitise its network stations, which can create further insights into the flows in the networks.

As metering methods become more sophisticated, there are increasing opportunities to fine-tune the way electricity network companies charge. We need a tariff that utilises these opportunities. The desire in the regulation to achieve cost-reflective and non-discriminatory tariffs that provide efficient network utilisation is not achieved with the price signals that today's power tariffs send. There is much to be done before we have price signals that help customers contribute to real value for the electricity networks - and the electricity system. In any case, the direction is very clear: we are moving further and further away from charging per light bulb.